-by Greg Hoots-

When one hears about Prohibition, the image that comes to mind is the decade of the “roaring twenties”, complete with gangsters toting machine guns and wild nights in the “speakeasy”. The era of Prohibition was a period of American history between 1919 and 1933 in which alcohol manufacture, sale, and possession were illegal in the United States.

National Prohibition became a reality in 1919 when the 18th Amendment to the Constitution was passed by Congress and approved by a national vote. There are few laws whose passage so instantly changed the face of America. Insofar as the alcohol manufacturing business was a vigorous industry when the 18th Amendment was passed, the law instantly destroyed many thriving businesses, created a large number of criminals, and provided a huge market for organized crime. Author Bill Bryson commented on the phenomenon, saying, “There’d never been a more advantageous time to be a criminal in America than during the 13 years of Prohibition. At a stroke, the American government closed down the fifth largest industry in the United States – alcohol production – and just handed it to the criminals – a pretty remarkable thing to do.”

The experiment in nationwide prohibition was not successful. While the law lessened the total gallons of alcoholic beverage sold in America, it did nothing to alleviate the problems that Prohibition sought to cure, and it created a huge business enterprise for the criminal element in America. At the same time, it also created a new class of criminals, adults whose only crime was the possession or sales of alcoholic beverages.

In Kansas, the experiment in Prohibition lasted for almost 70 years, with no greater achievement or success than the Federal effort to ban liquor. Long before the 18th Amendment created national Prohibition, individual states were creating state and local bans against alcohol. That effort took hold in Kansas in the 1870s when numerous religious organizations as well as temperance groups attempted to influence alcohol-control legislation in the state. The Kansas State Temperance Union (K.S.T.U.) and the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (W.T.C.U.) became powerful lobbying organizations in Kansas, and soon they began to influence legislation through the election of prohibitionist candidates. By the late 1870s the Republican Party endorsed statewide Prohibition, and in 1878 a Prohibitionist candidate, John St. John was elected governor. Upon taking office St. John called for a constitutional amendment banning alcohol in the state, and by 1880 the legislature had passed a statewide prohibition amendment. The law took effect on January 1, 1881.

The enactment of the new law did little to “dry up” Kansas. In virtually every town in the state, alcoholic beverages were readily available, and in fact, open saloons abounded. It was claimed by the press that in 1883 there were 43 “joints” operating in Topeka, including the Senate Saloon, located in downtown Topeka within walking distance of the Statehouse. The same was true across Kansas through the 1890s when saloons operated with bold abandon. The early saloon keepers soon came to an agreement with local officials; they would be arrested monthly and pay a fine, but they would be allowed to continue to operate. It was claimed that in some places the number of saloons actually increased after the inception of Prohibition.

The Prohibition movement gained a new foothold in Kansas in 1900 when Carry Nation, the divorced wife of a lawyer-turned-preacher, began a crusade against alcohol consumption. Nation made news in 1900 when she claimed that God had ordered her to Kiowa, Kansas to destroy a saloon, a task which she accomplished by using bricks to smash everything in the interior of the business. By 1901 Nation had organized a W.T.C.U. chapter and published her first anti-alcohol magazine. Later that same year Nation began using a hatchet as her weapon in the destruction of saloons across Kansas, and her second publication, The Hatchet, became very popular among Prohibitionists.

In addition to the work that Nation did promoting Prohibition, she was equally committed to the cause of women’s suffrage. Nation was instrumental in the movement in Kansas to give women the vote. Part of her motivation for this effort had its roots in her belief that women could become a powerful political force if they had the vote. And, insofar as women were the driving force in the temperance movement, Nation recognized that voting rights for women would greatly empower the cause of Prohibition, nationwide.

While the Kansas legislature initiated efforts to strengthen enforcement of liquor laws, huge loopholes still existed. One such exception allowed alcohol to be used as an ingredient in medicines, and druggists became the new purveyors of alcoholic drinks. In 1909 the medicinal alcohol loophole in the Kansas law was closed, as the crusade for a “bone dry” state gained support. In 1917 the Kansas legislature passed a “bone dry” law which was signed by Governor Arthur Capper. Two years later, the nation would follow course.

Efforts to enforce national Prohibition regulations were no more effective than they had been in previous forty years in Kansas. Yet, when Prohibition in America was repealed in 1933, Kansas did not follow suit. It was fifteen years later in 1948 before Prohibition was repealed in Kansas in a statewide referendum by a vote of 422,294 to 358,485. Even after the repeal, Kansas would continue to have a complex system of liquor laws, including local county-by-county options for Prohibition and the creation of complex private club regulations. Even today, Kansas has 13 dry counties, and the Kansas legislature has never ratified the 21st Amendment which repealed Prohibition in America.

Beer kegs and empty beer cases bearing the Val. Blatz brand name are stacked behind Horne’s saloon located at 226 Missouri Street in Alma, Kansas. Photo courtesy Eddie Meinhardt.

Wabaunsee County was never one of the “dry” counties in Kansas. During the Prohibition years, alcoholic beverages were readily available in Wabaunsee County. Alma native, Victor Palenske wrote of the situation in his 1975 essay, A Flint Hills Story, saying, “Although Kansas was dry, it was possible to have kegs of draft and barrels of bottled beer shipped in from Kansas City. The express trucks at the Rock Island depot were piled high with empty kegs a couple of times a week for shipment back to K.C. The story was told of a man sitting in a passenger coach of a stopped train, observing the many kegs, who remarked that he thought that Kansas was dry. The conductor supposedly answered, ‘this is not Kansas—this is Alma.’”

Conrad Miller, also known as Conrad Mueller, operated the Palace Billiard Hall when Prohibition was enacted in Kansas in 1881. Mueller was arrested for violating the prohibitory laws and closed his billiard hall, opening a hardware store in the same building.

When the first Prohibition laws were enacted in 1881, there were numerous esteemed Wabaunsee County businessmen who were regularly arrested for violations of prohibitory laws. A single arrest was motivation for some of those convicted of liquor violations to leave that line of work. With others, the arrests, fines and even imprisonment were just part of the cost of doing business. For many, liquor was the only business that they knew.

Peter Degan and his in-laws, the Horne family, operated a saloon at 226 Missouri Street in Alma for over 30 years.

In Wabaunsee County, the most notorious of all of the sellers of illegal alcoholic beverages was Bill Page of Eskridge. Bill Page was born in 1867 at Fairmount in Leavenworth County, Kansas where he spent his childhood, and his family moved to Eskridge shortly after the town was established in 1880. Bill Page and his wife, Mollie, raised four children, Gertie, Herbert, Winona, and Oneal. Page listed his occupation in early census records as a Laborer, but during the 1920s, after the family moved to Topeka, he and his oldest son, Herbert, listed their occupations as Teamster.

Bill Page, circa 1890-1900. Photo courtesy Joyceann Gray.

While Page was often referred to as a bootlegger in the local press, he was not a moonshiner or manufacturer of alcoholic beverages, but instead Page was a beer distributor, purchasing products from Kansas City breweries and reselling them at his establishment in Eskridge. Page also operated a liquid refreshment catering business for picnics, ballgames, and other outdoor events. In Eskridge his business was known as “The Lunch Room”, and some members of the press alleged that in addition to providing beer to his customers, Page “ran a crap game” at his establishment, and it was claimed that men could often be found playing cards there. Page operated his Lunch Room for about twenty years between 1895 and 1915, during a time when alcohol sales were illegal in Kansas, but not in Missouri.

The Horne family’s saloon was located in this building from the late 1880s through the early 1900s. In this view from the 1890s Joker Horne’s ice house is visible at the far left of the photo.

Bill Page was not the only operator of a “joint” in Wabaunsee County. From 1880 through 1920, there were multiple joints operating openly in Alma. The Horne family operated a saloon in the building located at 226 Missouri Street (now known as Palenske Hall) through the 1890s. After that building sold, John “Joker” Horne moved a half block east where he operated a joint called Froshien Hall which contained a “blind pig” located on the south side of the hall building. (Beer was sold in the joints while hard liquor could only be purchased secretly at a blind pig.)

A group of Alma men pose for Gus Meier’s camera in front of Froshien Hall, a saloon located on East 3rd Street in Alma. The small building at the far right was a one-lane bowling alley, while Joker Horne’s “joint” was located in the second building. Hendricks Hardware has a warehouse on this lot today.

A prominent businessman in Alma, John McMahan also operated a joint located at 224 Missouri (two doors south of Palenske Hall) from 1883 until his untimely death in 1902. McMahan owned the McMahan Telephone Exchange, Alma’s first telephone company, and he owned one of the town’s two livery stables. McMahan also served on the City Council and was the Alma City Marshal through the 1890s. All the while, “Johnnie-Mac” operated one of the liveliest joints in the county. While McMahan operated his saloon for almost twenty years, he was never sentenced to jail for violation of alcohol laws. While he was convicted on more than one occasion and paid a fine, prosecution proved to be problematic for the County Attorney who had difficulty in finding a jury that would convict “Johnnie-Mac.” The day John McMahan was buried, every business in Alma closed for his funeral.

A group of Wabaunsee County men pose in front of “Johnnie Mac’s” saloon in Alma, Kansas in this view, circa 1900. Saloon proprietor John McMahan is seen second from the left. Dr. R. W. Hull’s (fourth from left) wife was a prominent figure in the Alta Vista chapter of the W.C.T.U. Dr. Hull may not have shared her sentiments.

Bill Page’s “trouble” with the law began in the late 1890s. The first charge of violation of the prohibitory law filed against Page resulted in an acquittal in District Court in February of 1897. During the same term of the court, fellow Eskridge bootlegger John Lloyd and Alma’s John McMahan were tried for violating the liquor laws. Lloyd was convicted and paid a $100 fine, while the trial against “Johnnie-Mac” resulted in a hung jury, and the charges were not refiled.

A year later, in May of 1898, the County Attorney made a decision to punish three particular bootleggers, John Lloyd, Bill Page, and his cousin Joe Page, all of Eskridge. A curiosity in these three prosecutions was that the liquor sales in question all took place in either 1896 and 1897 and the County Attorney had waited a considerable time to file any charges. Lloyd faced two charges of selling alcohol in August of 1896, while Bill Page faced nine counts for sales made in the months of May, July, and August of 1897. Joe Page was charged with taking a wagon load of beer to Keene for a scheduled baseball game between teams from Keene and Auburn. When the men went to trial in October of 1898, Bill Page was convicted of six counts and acquitted of three, and was fined $600 and sentenced to six months in jail. The jury deliberated all night before delivering their verdict, which was characterized as a “tough sentence” by The Alma Signal. The County Attorney dropped all charges against John Lloyd.

As December arrived the county faced the reality that they would have to heat the jail for their only prisoner, Bill Page. They advised the prisoner that he could go home for Christmas and that if he didn’t commit any more crimes, he could remain free.

Freedom was short-lived for Bill Page. He had hosted a New Year’s Eve celebration at The Lunch Room, and on January 2nd Sheriff Treu arrested Page and his “club manager” James Powers for sales of beer at his New Year’s Eve party. Page was sentenced to 240 days in jail and fined $800, and Powers was given 60 days in jail and a $200 fine. It was reported in The Enterprise that the County Attorney claimed that he had “125 witnesses against them.”

Page had served his six months in jail, but he had no money to pay the $800 fine and $186.65 in court costs. Finally, he was released from jail only when he would sign a statement saying, “I, Wm. Page, do hereby agree to pay $8 a month until all my costs and fines are paid…” At that rate of repayment, Page would have been obligated to make a monthly payment to the county for the next ten years. And, of course, Bill Page’s only source of livelihood was in the operation of The Lunch Room and his catering business. So, he returned to work immediately upon his release.

Bill provided refreshments for a big dance held in Alma in April of 1900, and sales were brisk. Unfortunately, as the night wore on, a fight erupted, and the only man arrested was Bill Page. After Bill Page spent a few days in jail, the County Attorney discovered that his witnesses in the alleged assault would not testify, and Page was released.

It was back to work for Bill, and he landed a gig to cater a Sunday School picnic at Chief Stahl’s grove near Auburn, Kansas. Bill Page had left the picnic in a hurry, and the Shawnee County Sheriff issued a warrant for Page’s arrest that he sent to the Wabaunsee County Sheriff for service. On July 23rd, Under-sheriff Clayton arrested Bill Page in Eskridge. Three Eskridge men, J. Y. Waugh, C. L. Campbell, and William Henderson posted $100 each to bail Page out of jail. The trial was scheduled for November 26th, but unfortunately, Bill had worked late and missed the train for Topeka, missing his trial and forfeiting the bond. Then, he was taken into custody, and his trial was held on December 13th before a twelve-man jury. It took the jury two days to find Bill Page guilty of violating the prohibitory law, and he was fined $100 and court costs. Again, Bill had to return to work at The Lunch Room to support his family and pay his fines and legal costs.

Business returned to normal for Bill Page at Eskridge. In fact, business was better than ever. The summer of 1901 was a lively one, and the saloon business was good. On October 4, 1901 County Attorney Fred Seaman announced that the saloons in Wabaunsee County were closing for good. Apparently, numerous citizens across the county who had not appreciated the summer’s levity had written the Attorney General, demanding that the joints be closed. The Enterprise noted in a story headlined, Saloons are Closed, saying, “Mr. Seaman says the Attorney General forced him to take this step in response to the agitation that has carried on in this county since last spring.”

Bill Page and John Lloyd were arrested in early 1902 and promptly convicted and sentenced to six months, but in July of 1902 they were offered a parole from jail if they would sign an agreement “to quit the booze business for good.” The men were threatened if they violated this pledge, they would be jailed and “the Commissioners will provide a rock pile for their entertainment.”

With his pardon in hand, Page returned to Eskridge to The Lunch Room. He still needed to make a living. In November of 1902 F. M. Hartman swore a complaint against Bill Page, alleging that Page had threatened to kill him and had assaulted him with the intent to kill. Bond was set at $10,000. The newspapers of the day speculated that Bill Page had been stopped, once and for all, and that “he would be going to Lansing soon.”

Page hired Alma attorney C. E. Carroll who filed a Habeas Corpus motion in District Court, challenging the exorbitant bond. After some argument by Carroll and County Attorney Seaman, Judge Spielman reduced Bill Page’s bond to $1,500. Page’s father, Bill’s brother, Wesley Page, and Robert Sharp posted Page’s bond and he was released for trial. By the time the trial date arrived, Hartman, himself, had been arrested and charges against Page were dropped. Bill Page returned to Eskridge to work, and business was great. Summer was always such a good season in the drinking business.

In August of 1903 the Prohibitionist supporters were increasing the pressure to close Bill Page’s Lunch Room. They were now demanding that the Eskridge City Council force the County to close the business and put Page in jail. The August 28, 1903 issue of The Alma Signal reported, “It is known to everyone that there is a joint running in Eskridge, and it is being run by a paroled prisoner of the county. He receives large consignments of beer under the name “Grant Reed” and other fictitious names, besides having wagon loads of it hauled into town at different times. For the city council to keep silent on this question not only gives him leave to continue in this business, but it is an inducement for others to engage in it. All the city council need to do is to place an affidavit in the hands of the county attorney that “one William Page is engaged in the liquor business in this town,” and he will go back to jail…Who will be the first to speak?” The City Council spoke to the complaints, and Bill Page’s parole was revoked, and he was placed in jail in Alma, again. After spending a couple of months in jail, the County tired of his company and set him free again. He returned to Eskridge, going to work the next day.

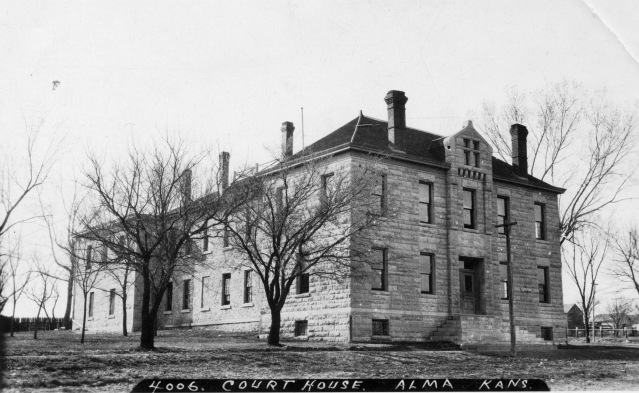

In April of 1905 the Wabaunsee County Commissioners established a new practice in social reform and rehabilitation of county prisoners. They created a rock pile where prisoners would swing a sledgehammer breaking large chunks of rocks into gravel. Various newspaper articles of the day indicated that the value of the rock pile seemed to be in its role as a deterrent to crime. There was little evidence that it was successful in that respect. The Alma Enterprise of April 14, 1905 noted, “The Commissioners done the right thing when they established a rock pile last week. The only criticism that could be made is on its location. It would have been much better in the opinion of many to have put it in one of the rear corners of the yard or on the city lot, instead of connecting it with the court house.”

The Wabaunsee County Courthouse is seen in this real photo postcard created by Zercher Photo in about 1910. At the far left of the image at the rear of the building one can see the top of the fence surrounding the rock pile. The County Jail was located in the back portion of the building.

The creation of the rock pile was an extraordinary failure as a tool of rehabilitation or punishment. The first problem was that “time on the rock pile” was generally more pleasant for the prisoner than occupying a cell in the jail. The men were less supervised inside the rock pile enclosure, they could enjoy the fresh air and sunshine, and above all, the rock pile was an easy enclosure from which to escape. At least five prisoners escaped the rock pile during its few years of existence on the courthouse lawn. Additionally, the creation of the rock pile enclosure, its maintenance, and the cost of policing the enclosure far exceeded the value of the gravel produced by the prisoners. One final observation concerning the rock pile in Wabaunsee County is that its use was exclusively set aside for African-American prisoners. Likewise, imprisonment for violation of prohibitory laws was reserved exclusively for black bootleggers, while Caucasian alcohol dealers paid their fines and continued their business.

By May of 1905 Bill Page’s business at Eskridge was doing well. One night a group of ladies from the W. C. T. U. went to Page’s house and began praying for him on his front porch. Angry that they had come to his home, Bill grabbed a driving whip and struck some of the women, chasing them from his porch. The temperance ladies fled, and reported the indiscretion to their husbands. Soon, a mob formed, intending to do Bill Page bodily harm. Sheriff Frey interceded and arrested Page, taking him to Alma for safe keeping. He was later fined $100 and sent to jail for 30 days. When he had been arrested at his home, a couple of barrels of beer were found on the premises, and Page was arrested on another liquor violation. It was Bill Page’s first opportunity to break rocks for the County.

Members of the Alta Vista Woman’s Christian Temperance Union pose for a photo at a club meeting held at “Mother Hull’s” home in about 1900. Quite by coincidence, Mrs. Hull’s husband, Dr. R. W. Hull was photographed with a group of his buddies posing in front of “Johnnie Mac’s” tavern in Alma.

Page was technically being held in jail on a violation of his written promise to the County Commissioners dated 1899, vowing to give up the liquor business. Page’s attorney, C. E. Carroll filed a writ of Habeas Corpus, and the Court released Page after only a week in jail.

Summer was always a good season in the beverage business, and the summer of 1905 was no exception for Bill Page. On July 3rd, Sheriff Ericsson executed a warrant for Bill Page’s arrest charging him with 21 sales of intoxicant liquors during the years of 1904 and 1905, while maintaining a common nuisance. Page’s bond was set at $2,200. To make matters worse, Page had a stock of beer at his home in anticipation of a 4th of July event which he was catering, and officers seized the beer and charged Page’s wife, Mollie with violating the prohibitory law.

The Pages faced the potential that both Bill and Mollie might face a jail term from the July arrests. Their attorney, C. E. Carroll explained that the County Commissioners just wanted the Pages out of the county permanently, and that he could get the charges dropped if they would leave. When the Pages’ trial began in the October 1905 term of the District Court, Carroll explained to the judge that the Pages had moved to Osage County where Bill had found employment with the railroad. Charges against both of the Pages were dismissed, but an injunction was placed against their property in Eskridge, banning the reopening of The Lunch Room, and a $100 lien was levied against their property for “attorney fees”.

Bill and Mollie Page and their children spent most of 1906 in Osage County; however, by the end of that year the Pages had returned to Eskridge. All of their family, Page’s father, brothers, sisters, and other relatives lived in Eskridge, and there was a substantial African-American community in the town. The Pages had returned to Wabaunsee County by Christmas of 1906, and within a month, Page was arrested on charges of violation of the prohibitory law and jailed. Bill Page faced trial in February of 1907, however, the charge was based on a two-year old affidavit and the original complainant could not be located, leading the judge to dismiss the charges against Page.

On July 5, 1907 a Santa Fe boxcar containing barrels of “two percent” beer was burglarized and several barrels of beer were stolen. ATSF detectives traced the beer to Bill Page’s home in Eskridge where several barrels of beer were discovered, and Page was taken to jail in Alma. Page faced trial in August, but the State was unable to prove that the beer found in Page’s home was the same product as that stolen from the boxcar, and when the trial was over, Page was acquitted and released from jail. Just two months later, Page became involved in an altercation between a friend of his and Eskridge’s Marshal Berry. A fight ensued and Page punched the Marshal, knocking him to the ground. Page was arrested, and when his house was searched after the arrest, beer was found on the premises, and charges of violations of the prohibitory laws were added to the counts against Bill Page. Page was sentenced to six months in jail for fighting.

In December of 1907 Sheriff Frank Schmidt was given the duty of jailing A. W. Rout, a Civil War veteran who was residing at the County Poor Farm. Rout was in desperate need of care, and he had allegedly become insane, requiring confinement and commitment. In a sworn statement given later, Schmidt recalled, “This man (Rout) was a county charge at the poor farm and who for some reason lost his mind and they were unable to care for him at the farm. There was a warrant in lunacy issued out of the Probate Court, then in due time a commitment to the jail. Now, this man should not have been put in jail. He should have been taken to some hospital and taken care of, but there was no way. He was the dirtiest piece of humanity that I ever seen and I could get no one to take care of him, so we made William Page do it, and in return we promised him that the county would pay him for it, and we think it right that they should.” Page cared for the elderly man, day and night, for twenty-five days. When Rout was finally transferred to a state institution, Page submitted his bill to the county for $1,250.

County officials were outraged and amused and offered payment of $8.42 for Page’s twenty-five days of work, and they withheld payment, crediting the amount against Page’s outstanding fines from his many past arrests. In the end, the County paid nothing to Page. Page, still in jail awaiting trial on another beer possession charge, hired C. E. Carroll to sue the County and Sheriff Schmidt for the unpaid bill. Carroll filed the suit in a municipal court that had a limit of $300 in damages, the amount which Page demanded in payment. The trial was held before Judge John Keagy on November 16, 1908, who rendered a judgement in favor of Page of $75 which the County paid.

During the first week of February in 1909, the newly elected Sheriff Ericsson raided Page’s house in Eskridge, having received a tip that the bootlegger had recently received several cases of “wet goods”. Sheriff Ericsson and his Deputies West and Tooker arrested Bill Page, returning him to the County Jail. Bill stood trial and was sentenced to 60-days in jail.

In March of 1909 Mollie Page left Eskridge, moving to Alma into the former home of William Moore. By the time Bill Page was released from jail in early April, the Pages had moved to Alma. Bill Page enjoyed less than a month of freedom before he was arrested on yet another charge of possession of beer and thrown into jail, again. In early August of 1909 Bill Page was “put on the rock pile” again. As the day was unusually hot and shade and water were running short, Bill Page escaped the rock pile yard and found a nice shade tree on the courthouse grounds under which he reclined, waiting for the Sheriff’s return. The Alma Signal of August 13, 1909 reported on the escape, noting, “Willie Page whom the county is entertaining for a couple hundred of days on a bootlegging count, made his get-away from the rock pile Tuesday morning. Just to show that his heart was free from evil intent—that he walked out merely to show that he could—Willie lingered near the jail and was soon picked up by Sheriff Ericsson, who rewards Willie’s joke with ten days on bread and water. Bill Page has spent probably half of the last fifteen years in jail, which probably has something to do with the sheriff’s refusal to regard this break as a joke.”

In the fall of 1909 Sheriff Ericsson executed a warrant for the arrest of John “Joker” Horne on violation of the prohibitory laws; however, Horne, tipped of his impending arrest, fled to Kansas City and then to California to avoid prosecution. The September 24, 1909 issue of The Alma Enterprise reported, “The sheriff locked up the old Froshien Hall Tuesday that had been run by John Horne for some time as a pool room.” With the 1902 death of “Johnnie-Mac” McMahan and the departure of Joker Horne from Alma in 1909, Alma was becoming dryer by the day, making for a good market for Bill Page.

New Year’s Eve had always been a big night of business for Bill Page, and 1909 was no exception. On December 31, 1909 Page was arrested for being drunk and disorderly and once again placed in the Wabaunsee County Jail.

Page spent the 1910s skirting the law with a spate of arrests for fighting or disturbing the peace being his primary offenses until 1914 when Page was arrested twice for possession of beer and being a nuisance. Page pled guilty in both cases and sentenced to six months in jail and fined $100 for each arrest. In 1917 and again in 1919 Page was charged with possession of beer and was convicted in the first case and acquitted by a jury in the second. In the spring of 1921 the Pages left Alma, moving to a farm near Bradford in Wilmington Township. By 1925 the Pages had departed Wabaunsee County for good, moving to Topeka where Bill Page and his son, Herbert, both found work as teamsters.

During the 70 years or so of Prohibition in Wabaunsee County, no single individual felt the wrath of the prohibitory laws more than Bill Page. The great disparity in judicial punishment given to black and white bootleggers in the early 20th century in Wabaunsee County was shocking in its overt application.

Click on any image below to view in a gallery format or a full-screen view.

Categories: Biographies, Early History, Flint Hills Stories

No pictures of Bill Page?

LikeLike

I wish I had a photo of Mr. Page. If one can be located, I would certainly place it in the article.

Thanks!

LikeLike

Wow! I wonder how much research you had to do to write this article. The historical approach taken by Kansas to control alcohol has been interesting to say the least. I still remember Vern Miller and his antics. — Anyway, great article.

LikeLike

Dan, it took months to write.

LikeLike