-by Greg Hoots-

In 1938 two German chemists, Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann, announced their discovery of nuclear fission and presented their theory to the world academic community. The importance of the discovery was not overlooked, neither by the political nor scientific communities. Virtually all of the world powers initiated scientific projects to investigate the future of nuclear power, be it for peaceful purposes or as an unthinkable tool of war.

In August of 1939, two Hungarian-born physicists, Leo Szilard and Eugene Wigner wrote a letter warning of the imminent development of a new type of bomb, more powerful than anything imaginable, which would be fueled by uranium. The physicists recommended that the United States aggressively begin the mining and acquisition of uranium ores while simultaneously advancing their research into nuclear science. Szilard and Wigner enlisted the support of world-renown physicist, Albert Einstein, who signed the letter which was then delivered to President Franklin Roosevelt.

Roosevelt acted immediately on the Einstein—Szilard letter, forming the Advisory Committee on Uranium (ACU), headed by Lyman Briggs, to investigate the issues raised in the letter and to make recommendations to the President. Two months later, the committee reported to Roosevelt, saying that uranium could become “a possible source of bombs with destructiveness vastly greater than anything now known.” In June of 1941 Roosevelt created the National Defense Research Committee, absorbing the ACU, and that committee became an arm of the Office of Scientific Research and Development. The directed purpose to this new department was to expand the engineering projects which would utilize uranium-235 and its related isotope, plutonium, for the purposes of creating weaponry.

In a matter of months, the Manhattan Project was officially born. The United States, with the cooperation of the United Kingdom and Canada, began the development of the first atomic bomb. The military arm of the project was led by Major General Leslie Groves, while the scientific development of the bomb was headed by Dr. Robert Oppenheimer, a professor of physics at the University of California at Berkeley. There were nineteen different sites across the United States and Canada where various parts of the “project” were developed. While each of the nineteen project sites was essential to the eventual development of “the bomb”, the three most important centers of the Manhattan Project included the scientific headquarters at the Los Alamos Laboratory, near Santa Fe, New Mexico, the Manhattan District Headquarters at Oakridge, Tennessee, where uranium enrichment was processed, and the Hanford Engineering Works in Washington State, where plutonium was produced.

In less than three years, the Manhattan Project had developed two distinct types of atomic bombs. “Little Boy” was a seventeen-foot long “Thin Man” design which used uranium-235 at its core, while the “Fat Man” bomb, almost six-feet in diameter, employed implosion against a plutonium core. “Little Boy” was dropped from a specially prepared aircraft on Hiroshima, Japan on August 6, 1945, and “Fat Man” was dropped three days later on Nagasaki, effectively bringing Japan to surrender on August 15th.

While the war was won, advancements in nuclear weapons continued at a furious pace, worldwide. In 1950 President Harry Truman authorized the further development of second-generation nuclear weapons known as “thermonuclear” bombs which gained their power in fusion of the core elements. Two years later, the first hydrogen bomb was tested at the Camp Desert Rock test site in Nevada.

United States Army soldiers watch as an early test of the hydrogen bomb was conducted at Camp Desert Rock, Nevada. Photo courtesy National Archives.

The thermonuclear design of the second-generation weapons had distinct advantages over the early nuclear bombs dropped on Japan. The new weapon design allowed the bombs to be much smaller in size while being far more forceful in their firepower. The weapon was considered cleaner, in that more of the radioactive fuel was expended as released energy, leaving less radioactive waste.

The ability to miniaturize the weapon was a most important advantage. Military leaders recognized that a weapon this small could be mounted in the reentry vehicle of a rocket, allowing it to be delivered to a target in a very short amount of time with no risk of loss of crew or carrier which was inherent in delivery by manned aircraft. The age of rocket science had arrived.

While rockets had been used in warfare since the tenth century, modern rocket science established a foothold in the early 1920s in the United States, Germany, Britain, and Russia. By the beginning of World War II, anti-aircraft rockets, surface-to-surface rockets and air-to-ground rockets had all been developed. By 1950, several nations had set their sights higher, seeking to launch rockets out of the atmosphere before sending a reentry vehicle back to earth. Military planners immediately realized the advantages of launching a rocket into space containing a miniaturized thermonuclear bomb which would return to earth inside the rocket’s nosecone. The idea had tremendous consequences. The rocket was sent into orbit in an arc, delivering the payload into space while traveling in opposition to the earth’s rotation, allowing it to be delivered to a target on the opposite side of the earth in less than thirty minutes after its launch.

The November 1957 issue of Engineer magazine, produced by the Westinghouse Corporation, featured articles related to rocketry and its future as a military weapon. Courtesy Paul Anderson.

In 1945 the U.S. Army Counter Intelligence Corps launched Operation Overcast followed by Operation Paperclip which had at the center of their objectives the identification and recruitment of over 1,500 former Nazi rocket scientists to develop advanced rocket technology for the United States military. The Russian military answered Overcast and Paperclip with Operation Osoaviakhim, “recruiting” over 2,000 Nazi scientists and engineers in the pre-dawn hours of October 22, 1946, most taken at gunpoint. The race to develop rockets to carry military payloads was underway. In the United States, numerous private aeronautic and engineering firms joined the effort to develop rocket-based weapons.

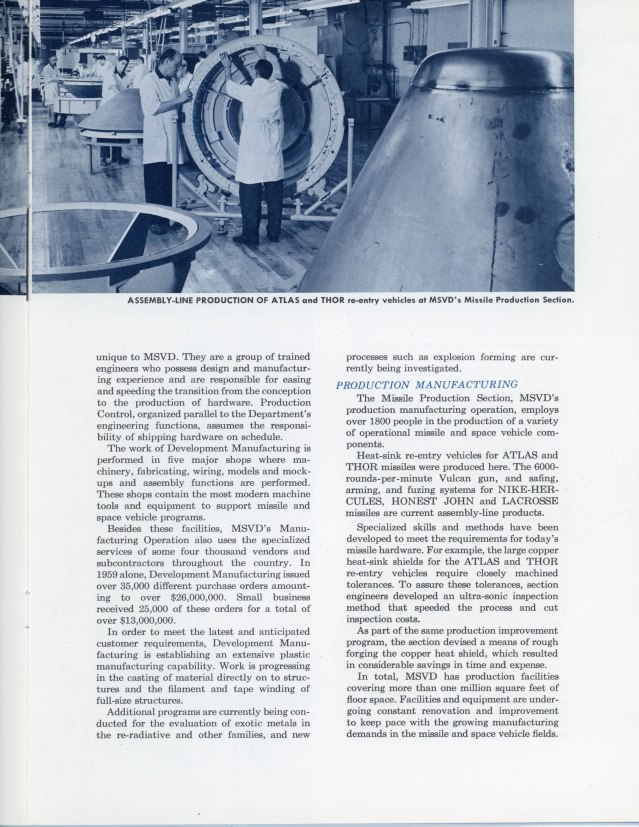

Corporations such as General Electric and AVCO began development of reentry vehicles, the nosecones of the rockets, which could carry payloads ranging from astronauts to a thermonuclear bomb. Intensive research and testing quickly resulted in the development of more and more powerful miniaturized bombs, which could easily be carried in the reentry vehicle. It was critical, however, that any such vehicle could withstand enormous vibrations encountered both in the launch and reentry to the earth’s atmosphere, while being protected from the intense heat generated by the friction of the capsule hurtling to earth.

The General Electric Company was a leader in the development of re-entry vehicles for rockets in the American nuclear arsenal. (Courtesy Paul Anderson)

The race to develop rockets which could carry men and weapons into space gained momentum throughout the 1950s. Development of short-range, medium-range, and long-range rockets matched the advancements in weapons systems for those missiles, and by the mid-1950s, designs had been penned for the development of America’s first Intercontinental Ballistic Missile, a rocket with a range of more than 8,000 miles. Moreover, the new missile was designed with the power necessary to carry a nuclear bomb as its payload.

The Defense Department, desperate for scientists, engineers, and inventors who could help solve the numerous difficulties inherent in rocketry, launched publications, proclaiming, “Inventions Wanted,” defining specific problems that the Air Force was attempting to solve.

This 1959 publication printed by the National Inventors Council presented specialized needs of the Armed Forces which required inventive solutions. (Courtesy Paul Anderson)

The contract to develop and manufacture America’s first intercontinental missile was awarded to Convair, a division of General Dynamics. It was at Convair’s missile manufacturing plant in San Diego, California where America’s first arsenal of rockets designed to carry nuclear weapons were built. While short and medium-range weapons had military significance in Europe, any missiles launched from the United States mainland would need to be of a long-range design that would travel into outer space when launched. Convair’s first intercontinental missile was dubbed the SM-65 Atlas.

This view of the Convair factory at San Diego shows Atlas missiles under construction. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

The first prototype Atlas-A, a single-stage rocket with no sustainer engine, was completed in 1957 and first tested on June 11th of that year. Eight of the type-A rockets were tested in 1957 and 1958, and half of the launches were failures. As research advanced in the areas of propulsion and guidance, designs improved in the B and C versions of the rocket. During testing, the Air Force conducted 24 launches of the Atlas with 11 resulting in failure. In 1959 Convair introduced the Atlas-D rocket, which was the first ICBM capable of carrying a thermonuclear warhead. Convair produced a stockpile of 211 Atlas-D rockets, and all of the Atlas-D rockets which were tested were launched from two facilities, Vandenberg Air Force Base in California and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida.

This inventory control document dated June 19, 1961 shows the details of the 211 Atlas-D missiles built by General Dynamics/Convair. Courtesy the Association of Air Force Missileers.

While the Air Force commenced a rapid series of test launches of Atlas-D missiles from both Vandenberg and Canaveral, Convair was already busy at work in developing the next generation of Atlas missiles, the Atlas-E. In addition to having more powerful engines, several differences set the E-model apart. The rocket had an internal guidance system that included a “stable table” containing three gyroscopes that operated continually inside the missile, providing information to an onboard computer which operated the directional Vernier rockets which guided the missile. Another notable difference was that the E-missiles were stored in underground horizontal “coffin” containers, which served as launch pads for the rockets. The first Atlas-E missile was flown on October 11, 1960, and the E-missiles were deployed in 1961.

The job of managing and deploying the nuclear-tipped intercontinental ballistic missiles was assigned to the United States Air Force. Between 1959 and 1962 the Air Force activated thirteen Strategic Missile Squadrons that were tasked with operating, maintaining, and deploying Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles. One of the units created was the 548th Strategic Missile Squadron, stationed at Forbes Air Force Base near Topeka, Kansas.

When the Air Force selected Forbes AFB to locate a missile squadron, plans called for a 3×3 configuration, which meant that there would be three remote launcher sites, each containing three missiles, with a single launch command center at each site. The three sites selected were in Osage County, Wabaunsee County, and Jackson County, Kansas. The early plan called for each site to be over 200-acres in size, containing three launchers and a launch control facility that might accommodate up to 100 airmen and officers. The 3×3 configuration was the common organization of the Atlas-D missile sites.

Before the land could be acquired for the three sites, the Air Force made a significant change in the configuration of the Atlas launchers at Forbes AFB. The new plan called for a 9×1 design with each of the nine launchers located in a unique remote location. It was believed that separating the nine missiles would decrease the squadron’s vulnerability to an enemy’s first-strike. It is noteworthy that the nine sites were not designed in a circle around Forbes AFB in a defensive stance to protect the base. ICBMs were not defensive weapons. Their location in a circle around the base was one of convenience for supplying the men and equipment necessary to operate each launcher every minute of the day, every day of the week.

As it was clear that the advancements in rocketry and nuclear weaponry had reached a point where deployment of the ICBM became a foreseeable reality, the Air Force began advertising within its ranks for its members to join one of the numerous Strategic Missile Squadrons that were being established at Air Force bases across America. While the coveted job of Air Force pilot was considered the most desirable, the new assignment as a missileman was considered equally prestigious.

For men like James Scott, a 2nd Lieutenant stationed at Clinton-Sherman Air Force Base, near Clinton, Oklahoma, the prospect of being an officer in one of the newly created Strategic Missile Squadrons had enormous appeal, and he sought an assignment in this new arm of the Air Force. Scott applied for missile training and an assignment with the 548th SMS at Forbes AFB.

Jim Scott was raised on the northern edge of the Flint Hills at Wamego, Kansas. After graduation from high school, Scott attended Kansas State College at Manhattan, Kansas. As Reserve Officer Training Corps was required for all male students for two years, Jim Scott chose the Air Force ROTC. Sixty-years later, Scott attributed that choice to his sense of style, “The Air Force had better looking uniforms.” After two years, Scott left Kansas State and transferred to Washburn University in Topeka, Kansas. His primary motivation for attending Washburn was to play college basketball. “I’m not sure what I was thinking,” Scott recalled, “I was only 5’9″ tall.” It was while at Washburn, however, that Jim Scott became very involved in the Air Force ROTC program. By the time he was a senior, Scott was the Cadet Commander for the Washburn Air Force ROTC. It was during Jim Scott’s junior year at Washburn that he met Shirley Clinkenbeard from Topeka, and near the end of his senior year, the couple married. After graduation in 1957, the Scotts moved to Oklahoma, as Jim had received his first assignment in the personnel office as a newly commissioned 2nd Lieutenant at Clinton-Sherman Air Force Base. While at Clinton-Sherman, the Scott’s family grew as they had two children. When the call came in 1959 for men to join the missile program, Jim Scott sought the assignment, and he was chosen to become a member of the elite force.

Scott was sent to Sheppard Air Force Base at Wichita Falls, Texas for six weeks of Phase I Missile Training, followed by six weeks of Phase II Missile Training at Vandenberg Air Force Base at Lompoc, California. Upon return to Forbes, Scott spent six more months of on-the-job training at the Missile Assembly Building at Forbes, the headquarters of the 548th Strategic Missile Squadron.

This 1961 view from the Sheppard AFB Atlas training complex shows an Atlas-E missile hanging from a boom in a missile bay. Sheppard was one of the two main training facilities for the Air Force’s missile squadrons. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

When the Scott family returned to Topeka there was no available on-base housing for the newly promoted 1st Lieutenant, so the Scotts, now a family of four, purchased a home on Southwest 32nd Street in Topeka. Years later, Jim Scott remarked that “I had joined the Air Force to see the world, and I found myself back in Topeka.”

The first major construction effort to accommodate the 548th SMS at Forbes AFB came in August of 1959 with the release of $750,000 by the defense department for the construction of the Missile Assembly Building, located in the former base supply depot on the west side of Highway 75. The building was divided generally into two sections, maintenance and operations. The 548th SMS command also operated from this building, as did the launch crews who served their duty assignments deep in the bowels of missile launchers, buried in the Kansas Flint Hills.

The 548th Strategic Missile Squadron operated from a renovated building in the old supply depot at Forbes Air Force Base. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

Soon, additional expenditures were approved for the squadron in the form of $100,000 for a microwave installation, $600,000 for a Missile Reentry Vehicle building, $360,000 for a storage building, $72,000 for a liquid oxygen factory, and an additional $250,000 for further improvements to the Missile Assembly Building.

Each Atlas missile launcher site contained a minimum of nine men at all times. A five-man launch crew and four armed guards were at the missile site around the clock. A launch crew manned the site for a 24-hour shift, known as a “tour”. At the end of each tour, a new five-man launch crew arrived from Forbes, relieving the previous team. Two armed guards, members of the Combat Defense Team, patrolled the 20-some acre site on the surface, while the two additional guards slept inside the site. The 548th SMS had fifty-eight five-man launch crews in its ranks. The crews were divided by command into three sectors with each sector containing three missiles and fifteen five-man launch crews. There were also three five-man Standboard crews that acted as quality control teams, performing audits, inspections and certification tests on all of the active crews. The five remaining crews were not combat-ready and contained men yet to be receive certification.

By 1960, the work of construction of the nine underground missile launchers proceeded with urgency. Nine sites were selected for the launchers, and the Air Force made no effort to hide a thinly veiled threat that any objections to the acquisition of the land needed for the missile sites would not be entertained because of the extreme urgency of the project for the national defense. The locations of the launchers, the Air Force contended, were chosen for their positions relative to specific targets of the missiles. The site numbers of the missile sites included 1. Rock Creek, 2. Worden, 3. Waverly, 4. Burlingame, 5. Bushong, 6. Keene, 7. Wamego, 8. Delia, and 9. Holton. The sites ranged in distance from Forbes AFB between 35 and 56 miles.

This map, produced by the Air Force, shows the locations of the nine Atlas missile launchers operated by the 548th Strategic Missile Squadron at Forbes Air Force Base. Courtesy Paul Anderson.

On April 5, 1960, the Air Force awarded a six-million-dollar contract to the Independent Telephone Association, Inc, a group of five independent telephone companies, for the construction of a direct circuit link between the nine missile sites and the squadron headquarters at Forbes AFB.

On June 10, 1960, a one-day work stoppage struck the nine construction sites as the Engineers and Architects Association called a national work stoppage against Convair. Labor unions representing all of the construction companies building the nine sites refused to cross the EAA picket lines.

In this 1960 view of construction of one of the Forbes launchers, the concrete walls of the missile bay have been poured but the floor has not. This appears to be Site #6 at Keene. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

On July 1, 1960 the 548th Strategic Missile Squadron stood up. The squadron was comprised of approximately 700 men. The press initially reported the strength of the unit at 435 airmen and 128 officers. In addition to the numerous subcontractors involved in the construction of the silos and the installation of the electronic and hydraulic equipment, the missiles were installed in the launchers by Convair specialists.

In August of 1960, contracts for a total of $747,000 were approved by the Kansas State Highway Commission for the construction of paved roads to each of the nine missile sites. Such action was necessary to make access to the sites possible for the transporters which moved the 72-foot long rockets from the Missile Assembly Building at Forbes to their launchers. The missile site road bids were administered by the State Highway Commission, but the Air Force paid for the road work.

In this 1961 view from one of the Forbes missile sites, one can see the testing of the missile erection equipment while the site was still in civilian hands. This missile, often called a “whalebone” was a non-operational version used to test the erection booms on newly constructed launchers. Notice that one of the booster engines is missing from the rocket. This photo was taken by General Dynamics photographer, Dave Mathias. Photo courtesy Paul Anderson.

On October 26, 1960, members of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers struck all nine missile site projects in a dispute between Hoisting Engineers Local 101 of Kansas City and the IBEW Local 304 of Topeka. The strike stopped work at the missile sites until U. S. District Court Judge Arthur J. Stanley, Jr. issued an injunction on November 8, 1960, halting the strike until the dispute could be resolved by the National Labor Relations Board.

As 1961 approached, contractors continued to work frantically on the nine launcher complexes. Some sites were far ahead of others in the construction process with the Burlingame site being the closest to completion, while the Waverly site was the least complete.

An Atlas-E missile is seen here being loaded into the cargo bay of a C-133 transport plane at Vandenberg AFB, California. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

On January 24, 1961, the first Atlas missile arrived at Forbes AFB from Vandenberg AFB in the belly of an Air Force C-133 transport. After carefully unloading the wrapped missile, the rocket was loaded on a transporter and moved across Highway 75 to the Missile Assembly Building. More missiles followed. The 548th maintained ten rockets in their arsenal, one located at each launcher and a spare located at the Missile Assembly Building at Forbes. As each site reached completion, a missile was installed horizontally in the missile bay by an Air Force crew, and Convair engineers then attached the electrical lines and plumbing to the rocket. The last component of the sites was the launch console and the logic units, a huge bank of computers that managed the launch systems. After each missile was installed, wired, plumbed, and manned, an ordinance crew installed the reentry vehicle or nosecone containing the nuclear warhead onto the rocket. As each site was thus completed, it was placed on alert.

The first Atlas-E missile to arrive at Forbes Air Force base is seen in this January 24, 1961 photograph as it is being removed from a C-133 transport plane. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

Site 548-4 at Burlingame received rocket number 486, the first Atlas missile to be installed into a base in Kansas. The Manhattan Mercury of April 14, 1961, reported on the delivery, “An Atlas ICBM has been raised into firing position for the first time at the missile base near Burlingame, which is the first of an eventual 39 launching sites under construction in Kansas. The missile was positioned and raised as part of operational checkout tests at the site which is part of the Forbes Air Force Base complex around Topeka.” A convoy of Air Force and Highway Patrol vehicles transported the rocket from Forbes AFB to the Burlingame launcher site. The April 12, 1961 edition of The Kansas City Times reported, “Spectators lined the streets in Osage City, Kansas as the big Atlas missile rolled ponderously past on the route from Topeka to the launching site between Burlingame and Osage City. The 18-vehicle convoy covered the route in about two hours.”

This photo, dated April 12, 1961 shows missile number 486 being installed in Site #4 at Burlingame, Kansas. This was the first ICBM installed in a launcher in Kansas, and the first Forbes missile placed on alert. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

Site #7 at Wamego was unique in several aspects. First, it was the only one of the nine sites which had electrical power provided to the silo by a public utility, in addition to the two generators contained within the site. The remaining eight sites were powered exclusively by generators. The Wamego site was also the most distant from Forbes AFB, listed in Air Force documents as being 56-miles from the base.

In this 1960 view of the Wamego Site #7, one can see that the launcher was nearing completion. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

Most importantly, the Wamego site was designated as the alternative command post for the 548th SMS, should the command facility at Forbes come under attack. While all nine of the missile sites had hard-wired telephone wires linking them Forbes Field, and each had a direct communication line to receive orders from Strategic Air Command headquarters at Offutt AFB, the Wamego site also had a single side-band console that allowed the operator to talk to any SAC site in the world.

This “red telephone” located at Offutt Air Force Base in Omaha could communicate directly with every Strategic Air Command facility in the world. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

All of the nine sites were designed so that the nose of the missile, when lying prone in the missile bay, was pointing directly to the north, and the north star had to be visible from that vantage point. This was necessary for the synchronization and setting of the internal gyroscopes in the rocket which guided it in flight. A highly secretive group of guidance specialists from “the other side (east side) of the base” where ordinance was also stored, did all of the calibrations of the onboard gyroscopes, the heart of the internal guidance system. When the missile was installed in Site #1 at Rock Creek, members of the guidance team discovered that because of the topography of the land located north of the site, the north star was not visible from the missile bay. To remedy this situation, the Air Force purchased land two-miles north of the missile site on which they constructed a tower containing a large mirror which allowed the missile to be calibrated relative to the north star.

This example of “silo art” was produced by an unidentified crew member from Launch Site #1, Rock Creek. Courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

The spring of 1961 saw installations of Atlas rockets in the nine sites operated by the 548th SMS. On July 5, 1961 one of the last Atlas missiles to be installed at Forbes was backed into the missile bay at Bushong, Site #5. Three weeks later, on July 28, 1961, the Air Force officially accepted all nine sites from Convair. Although several of the sites were on alert by the end of summer, it was not until October 16, 1961 that the Air Force officially declared all of the nine missiles operational, implying that all of the sites were then on alert.

In the foreground, Kansas farmers seem oblivious to the erected Atlas missile just over their shoulders. This incredible photo was taken by Dave Mathias in his capacity as a General Dynamics photographer and is dated 1961. Photo Courtesy Dave Mathias.

Daily life at the missile sites was one of monotonous routine and extreme vigilance. The launch crew consisted of five members, and each member had very specific duties and responsibilities. The five members included the Missile Combat Crew Commander (MCCC), the Deputy Missile Combat Crew Commander (DMCCC), the Ballistic Missile Analyst Technician (BMAT), the Missile Maintenance Technician (MMT) and the Electrical Power Production Operator (EPPO). All five members of the launch team wore white coveralls. The MCCC and the DMCCC both wore sidearms, and each wore a plastic holder on a chain around their necks in which the ultra-secret nuclear codes were sealed. The Crew Commander and his Deputy sat side by side at a launch console. The console table contained numerous checklists that both men followed precisely during all launches and simulated launches. The face of the console had a minimum of four stopwatches attached, and as each function of the launch sequence was initiated, the men would use the watches to time every action to the second. Precision was vital to a successful launch.

In this view from the launch control room of an Atlas-E missile site, one can see the launch console in the left foreground. At the far right is the control panel that managed the physical plant. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

When the missile sites went on alert in the summer of 1961, 1st Lieutenant Jim Scott was a Deputy Commander of launch team R-15 at the first site activated, Burlingame #4. In several months, Scott received a promotion to the rank of Captain, and he became the Missile Combat Crew Commander for crew R-02, assigned to Waverly, Site #3.

On the days when Crew R-02 was scheduled for a tour, Captain Scott reported to the Missile Assembly Building for a 7:00 am briefing. Scott and his deputy commander attended the briefing while the three non-commissioned crew members attended a more abbreviated meeting before attending their duties in preparation for their 24-hour tour in the missile site. The first item of business in Scott’s briefing was that all of the launch officers in the room would receive a coded message that each would decode. Every launch commander and their deputy would compare their decoded message, and they had to be a perfect match. If any launch officer made an error in decoding the message, they were removed from the launch team and immediately replaced with a substitute crew member.

Then, the launch officers would be briefed on military intelligence information, worldwide. At the time, during the first half of the 1960s, the intelligence briefing usually gave information concerning Vietnam. All of the information received at the officers’ briefing was a step higher than TOP SECRET, being classified as TOP SECRET-CRYPTO. While the officers attended this meeting, the non-commissioned officers would load all of the supplies that the crew would need for the next 24-hours into an Air Force vehicle. This primarily included all of the food that the team would consume. In addition, if there happened to be any documents or other crew materials that needed to be transported to the site, it was loaded into the car.

The Sikorsky H-19 helicopter was the first method of transport used to move launch crews to and from the missile sites at Forbes AFB. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

Originally, when the nine missile sites opened, the crews were transported from Forbes to the launcher by Air Force Sikorsky H-19 helicopters. In that the sites were generally less than fifty miles from the base, such a trip was a short one. However, when the helicopters were grounded on numerous occasions due to weather conditions, and a decision was made to switch the crew’s method of transportation to the De Havilland DHC-2 Beaver aircraft.

The de Havilland DHC-2 Beaver aircraft, a small transport workhorse, was used to transport launch crews to the missile sites for a short time in 1961. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

The small single-engine, high-wing, aircraft was ideal for short takeoffs and landings, such as those needed to land on the short dirt landing strip at each site. Again, the weather seemed to cause difficulties in getting the crews to their assignments in a timely fashion. Thus, an Air Force car became the transport of choice for members of the launch crews.

When the briefing was concluded, the launch crews departed Forbes, and generally the senior non-commissioned officer drove the car containing the crew members. When Scott’s crew arrived at the missile site, the car approached the gate, and the driver had the daily password he received at his briefing. Some drivers wrote the password on the palm of their hand. The armed guard at the gate relayed a message by walkie-talkie to the Commander in charge of the site, identifying Scott’s team, and the Commander on duty opened the electric gate from the controls located next to the launch console. Scott’s five-man crew entered a large steel door located at the bottom of the entry ramp which locked behind them, trapping them in a small entryway. The MCCC seated at the launch console visually inspected the men via a closed-circuit camera before remotely unlocking the second door, allowing the replacement crew access to the interior of the site through a long, galvanized metal tunnel.

This view, dated 1961, looks down a long access tunnel at one of the Atlas-E missile sites. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

The MCCC and the DMCCC on duty would simultaneously remove the sealed nuclear codes that hung on a chain around their necks and hand them to the two launch officers of the replacement crew, who then immediately assumed control of the site, and the 24-hour tour began. Vigilance was a constant companion of the men who operated the Atlas launchers. The crew was allowed only fifteen-minutes to launch their missile, and it required extreme precision on the part of every crew member to be successful. Jim Scott recalled his mindset, “My job was to launch the missile. I’ve got to do everything I can do to make it happen.” This author asked Scott if had a lot of anxiety about the nature of his job when he was the Launch Commander. Without hesitation he replied, “I really worried about one thing, what if we get the order to launch and we do everything, and it doesn’t work, it doesn’t launch, what would I do then? Should I go out and try to figure why it didn’t work, would we try again? There was no training for that possibility. I thought about that a lot.”

To guarantee that the crew would be successful if they were called to launch their missile, Captain Scott put his crew through repeated simulated launches during every tour at the launcher. Everyone had a job to do, and they practiced launching the missile over and over again. The routine practices involved repetition of all of the precisely timed tasks required to launch the missile. The team performed more sophisticated training simulations when a maintenance team would switch the missile’s computers into Launch Signal Responder’s Mode, taking the rocket off alert while disengaging the missile from the control console. The Launch Signal Responder units would simulate the entire launch through the point of “missile away”, while the crew’s launch console’s gauges would read as if an actual launch were happening. As a part of routine maintenance of the rocket, “wet tests” were also performed where the rocket was erected and loaded with RP-1 fuel and Liquid Oxygen. The simulation not only allowed the rocket to be serviced, but it provided an additional level of training for the launch crew.

The logic units, seen here, controlled not only the rocket during actual launches, they were also used to allow realistic simulated launches. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

The room located on the east side of the missile bay contained tanks of volatile fuels and gasses, including RP-1 (jet fuel), liquid oxygen (super-cooled to -297 degrees), liquid nitrogen (-320 degrees), helium, and gaseous nitrogen. Each fuel had to be loaded into the rocket for a very specific number of seconds, no more and no less, hence, the need for the stopwatches on the launch console. The Missile Maintenance Technician monitored pressurization of the rocket tanks, while the BMAT stood at the logic units, a 30-foot long bank of computer units necessary to launch the missile. The fuel tanks inside the missile were so thin-walled that they were subject to collapse as the fuel was expended during a launch. The pneumatic system infused helium into the fuel tanks during launch to fill the empty space created by the burning fuel. During countdown, liquid nitrogen was loaded into globes which kept the helium super cold during the launch. The helium would be converted to a gas by the heat from the engines, which would then fill the fuel tanks with lightweight gas as the heavy fuel was being expended during the five-minute powered flight.

In this view of an Atlas-E launch console, one can see four stopwatches attached to the console, used by the launch team to time missile erection and fuel loading. Checklists abound on the desktop and are attached to the console face at the far right. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

The fifth man on the team, the EPPO worked in the power room of the silo, controlling the generators. While one generator ran continuously to provide power to the missile site, the second unit was only required when the missile was being erected, loaded with fuel, and launched. It was the EPPO who was responsible for starting the second generator and, more importantly, he had to precisely synchronize both generators so their outputs were perfectly matched.

In this view of the generator room at one of the Atlas missile sites, one can see the two 100-kilowatt-hour units mounted on concrete piers. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

Jim Scott’s team practiced simulated launch procedures using checklists carefully timing all of their actions. About once a month, the team practiced opening the overhead door and erecting the missile. The team had checklists that led them through every procedure, despite the fact that every member of the team had every part of their job committed to memory.

A maze of pipes and pumps transported fuel from on-site storage tanks to the rocket’s fuel tanks during launch preparation. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

At the end of their 24-hour tour, a new launch crew arrived to relieve Captain Scott’s team which then returned to Forbes AFB. When the squadron was organized, it was planned that a launch crew would work one day on duty, followed by four days off duty. Unfortunately, due to the staffing problems common to every large organization, crews or crew members were often required to report back for another tour after only three days of relief.

When asked what it was like to be locked underground in a missile launcher for 24-hours at a time, Jim Scott replied that he never really thought about it much while he was there. It was much like working in a building without windows. Scott said that the real difference was noticeable when he emerged from the site at the end of the tour. “What I noticed was the fresh air on the surface…the air smelled so different…so fresh.”

Life at the nine missile launcher sites was not without incident. Information concerning accidents, incidents, fires, explosions or loss of life was held particularly close to the vest by the Air Force. Even today, more than a half-century after their decommissioning, details of incidents are sketchy.

The first incident which occurred at one of the nine Forbes sites occurred on September 27, 1961, just two months after the missile went on alert. A contemporaneous report of the event was made by the Air Force, dated 10-01-1961, saying, “ON 27 SEP 61, AN INCIDENT OCCURRED AT MISSILE COMPLEX 548-4 WHEN A BULKHEAD CRACKED WHILE THE CREW WAS PERFORMING THE FLUSH AND PURGE OF BOOSTER ENGINE NUMBER 2.” The bulkhead divided the internal compartments of the rocket, separating the volatile fuels and gasses. The bulkhead material was so thin that exact pressures had to be maintained on both sides of the divider, and constant monitoring was required. In this case, the desired pressure was lost, and the bulkhead inverted in shape, resulting in the missile being taken off alert. The missile was removed to the Missile Assembly Building at Forbes, and a spare rocket was installed at the Burlingame site, restoring the site to its on alert status. The damaged missile was none other than rocket No. 486, the first ICBM to be installed in a silo in Kansas.

On Tuesday, March 13, 1962, an incident occurred at Worden Site #2. Described in newspapers of the day as both a fire and explosion, the Air Force immediately issued denials that either ever happened. The Air Force’s initial denial was voiced in the Garden City Telegram of March 14, 1962, saying of the report of an explosion or fire, “It was an erroneous report, originated when smoke from a motor was carried through ventilators,” said Capt. Albert E. Hanneman, public information officer at the base.” The story began to change slowly as The Emporia Gazette of March 15, 1962 quotes an Associated Press story by The Topeka Daily Capital, “The Topeka Daily Capital said today an alarm at an Atlas missile site was more than just a ‘smoke scare’. The newspaper said it had learned the complex and costly Atlas missile had completely ruptured as a result of a malfunction within the missile itself. Air Force officials had reported Tuesday night that the alarm which sent emergency equipment scurrying to the launch site was due to smoke from an overheated electric motor. Later officials said the malfunction occurred inside the missile and caused it to buckle. The newspaper said the warhead was removed Tuesday night and the missile itself may be returned to the factory for investigation by a team of experts to determine what caused the malfunction.”

Jim Scott was quite familiar with the incident at the Worden site, as a personal acquaintance was present when the event occurred. The Stone Crew, the lead Standboard Crew, were performing routine checks of the missile’s electrical systems while the rocket lay horizontal in the missile bay. The Stanboard DMCCC, 1st Lieutenant Larry White was performing checks, carefully following a checklist created by General Dynamics and provided to the Air Force. White read each of the checklist orders aloud, and as he performed each task, he place a check-mark with a grease pencil beside each directive. Lieutenant White was seated against one of the rocket’s booster engines as he performed the checkout, and without warning, the booster engine exploded. Tiny sparks of stray electrical energy were created in the circuit-testing process, itself, and insofar as the system wasn’t grounded at the appropriate times to drain the stray voltage, a large enough spark was created to ignite the pyrotechnics of the solid propellant gas generators (SPGG) which surrounded the rocket engine. The explosive charges, when triggered correctly, send the turbine blades into motion, starting the rocket. In this case, however, since the rocket contained no liquid fuel which served to lubricate the engine, one of the booster engines exploded, causing the turbine blades to break apart, damaging the missile both internally and externally.

When Lieutenant White opened his eyes after the explosion, he was horrified to see the missile’s nuclear nosecone lying on the floor of the missile bay. A piece of one of the turbine fan blades was embedded in the missile bay wall. The explosion triggered an extensive investigation by the Air Force and General Dynamics. It was determined that White had followed all of the procedures contained in the checkout list, and that the fault was due solely to an inaccurate list created by General Dynamics.

The rocket in the Worden site was removed to the Missile Assembly Building, the debris removed, and a replacement rocket was moved to Worden and installed in Site #2.

In this 1960 view of an unidentified missile site located near Forbes AFB, the metal framework for the 400-ton door which covered the missile bay is visible. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

On November 26, 1962, the only reported death at one of the nine missile sites occurred at site 548-4 at Burlingame. The Latrobe Bulletin of November 27, 1962 printed a United Press International story detailing the death of a Combat Defense Team guard at a Forbes missile site, “A Doylestown, Pa., airman accidentally shot and killed himself Monday while on guard duty at an Atlas “E” missile site south of here. Authorities identified him as Airman 2C William P. Walsh, 19, who was stationed at Forbes Air Force Base here. He was serving a duty tour at the missile site in Osage County. Air Force officers said Walsh was walking his duty post when his gun discharged. The bullet hit him in the throat.”

Jim Scott remembered the incident distinctly. It was almost 9:00 am and Jim Scott’s crew had spent 24-hours locked inside Site #4 at Burlingame. A replacement crew had arrived and were met by both guards as they passed through the entry gate. The crew proceeded to the entry door while the two guards walked from the closing gate. The relief crew was given access to the site through the pair of heavy steel doors, passing through the access tunnels to the launch control room. Scott’s crew was ready to leave, and the MCCC and the DMCCC of the retiring crew removed the nuclear go-codes from around their neck, presenting them to the replacement launch officers who immediately put them on, thus taking control of the launch site. Within minutes, the call came on a walkie-talkie from one of the guards on the surface, saying that the other guard had shot himself. The newly seated MCCC immediately contacted Forbes, and a flight surgeon was dispatched by helicopter from the Air Force Base. Scott and his team went to the surface, loading their personal belongings into their Air Force vehicle, just as the helicopter was landing. He recalled that the surgeon exited the helicopter and walked to the spot where the wounded guard lay on the ground and took one look at the airman, saying, “this man is dead.” The deceased airman was loaded onto the helicopter and returned to Forbes. Further questioning of the second guard revealed that that he had seen the other guard snag the bolt of his rifle on some brush, advancing a shell into the chamber. The first guard insisted that no such thing had happened and that his rifle was not loaded, and he placed the barrel under his own chin, pulling the trigger. One round was in the chamber.

An incident which occurred on June 2, 1963 was acknowledged in the Forbes Air Force Base newspaper, the Forbes Sky Schooner of August 30, 1963. The story, titled, “Top Missile Crew” identifies the members of a launch crew R-37, named Second Air Force’s Missile Crew for the month of July. The caption for the photo of the crew notes, “The crew was picked for its immediate reaction in possibly averting a missile incident on June 2 and for their outstanding performance of duty in routine and hazardous situations.” No details of the incident are given in the paper. The crew worked at both Site #9 at Holton and Site #1 at Rock Creek.

FORBES SKY SCHOONER, August 30, 1963 TOP MISSILE CREW–Crew R-37 of the 548th Strategic Missile Squadron, Forbes, has been named Second Air Force’s Missile Crew of the Month for July. Top row (left to right), are TSgt, Lee A. Fowler, A1C Kenneth R. Osborne and SSgt. Clarence Jones, Sr. Seated (left to right), are 1st Lt. P. K. Ware and Capt. H. L. Williamson. The crew was picked for its immediate reaction in possibly averting a missile incident on June 2, and for their outstanding performance of duty in routine and hazardous situations. (Official USAF Photo)

On August 9, 1963, while a maintenance team worked on routine checkout procedures on the missile in Site #6 at Keene, an explosion occurred as a maintenance crew was performing a checkout procedure on the rocket. The pyrotechnics of one of the engines ignited while a technician was checking voltage on circuits on one of one of the rocket motors, causing it to explode. It was virtually an identical incident as the March 13, 1962 explosion at Worden Site #2. As at Worden, a clean-up team was created, the missile was removed, and a replacement rocket was installed at the Keene launcher.

Site #6, located at Keene, Kansas was still in civilian hands when this photo was taken by General Dynamics photographer, Dave Mathias in 1961. Photo courtesy Dave Mathias.

Despite the various incidents which occurred at the Atlas sites operating at Forbes AFB, in every case the sites were returned to normal on-alert status in short order with the installation of a spare missile.

In addition to the dedicated telephone lines that linked all of the nine missile sites to the command post at Forbes AFB, each missile site also contained a “squawk box”, a type of electronic speaker which linked the missile site directly to SAC command at Offutt AFB. All of the messages received from this device were encoded, and additionally, each message was given a color code which designated current conditions. A white color coded message, for example meant that the site was undergoing a training operation. A blue color code signified, “prepare for war”. If the squawk box message were coded red, the nation was at war.

There were only two times that messages from Offutt carried a blue code. The first was during the Cuban Missile Crisis in October of 1962, and the second was November 22, 1963, the day that John Kennedy was assassinated. Captain Jim Scott was on assignment, attending a Squadron Officers’ School in Montgomery, Alabama during the 1962 confrontation with the Soviet Union at Cuba; however, Scott was on a duty tour at the Burlingame Site #4 on the day that President Kennedy was killed.

At all times, there were two armed guards on the surface of the missile site while the remaining two were inside the site, sleeping. It was an accepted practice that the guards on the surface could carry transistor radios while they were on the surface performing guard duty. Each of the guards carried a walkie-talkie with which they could communicate with the Launch Commander inside the site. At 12:30 pm, Captain Scott heard the walkie-talkie’s blare with a message from the surface, the President of the United States had been shot. At the very instant that the words came from the walkie-talkie’s speaker, the squawk box emitted an audible alert that a message was arriving, and it was coded blue. Scott grabbed his pen to begin decoding the message, although he knew exactly what to expect. The President was dead, and the new President was aboard Air Force One, the conditions were blue, prepare for war. The five men manned their stations, ready for a countdown to launch.

Each missile site contained a television set in the personnel area, but Captain Scott always maintained a strict rule that the set could not be watched during the day, even by the resting guards. The sleeping guards had heard the message from the guards on the surface, and they wanted to turn on the television. Scott agreed to allow the television to be turned on for ten minutes. When the guards turned the set on, Walter Cronkite was just beginning his infamous announcement that the President was dead. The launch crew remained at their posts, anxiously awaiting their orders from Offutt. After a total of six hours a new message came from Offutt coded green, advising the crew of the lowering of the threat level. Despite the message, the launch crew remained ever vigilant and were at a higher level of preparedness due to the uncertainty of what might come next. The next morning by 9:00 am, a new crew arrived, and the five men who had spent the previous 20-hours on the brink of nuclear war went home.

Throughout 1963, the Air Force had continued testing the Atlas missiles at their Vandenberg AFB launch facility. The 1963 test flights had not been successful. The Hays Daily News of October 29, 1963 reports on the failures of the Atlas tests, “Air Force demonstrators today sought the cause of the sixth straight failure of an Atlas missile. The rocket tumbled out of control shortly after it was launched Monday night in an attempt to boost a deceptive new warhead on a 5,500-mile flight. The warhead was tapered to reduce the image which might appear on an enemy radar screen. The failure followed five straight Atlas fizzles at Vandenberg Air Force Base, Calif. Officials had no explanation for the failures.”

In January of 1964, Captain Jim Scott notified the Air Force that he would not be renewing his enlistment scheduled to expire in the summer. Scott had decided it was time for him to leave the military and pursue a civilian career. Upon giving notice of his intentions to the Air Force, Scott was relieved of his role as Missile Combat Crew Commander, and he served his last six months in the Air Force as an attaché to an Air Force Colonel at Forbes.

Captain Jim Scott and his wife, Shirley, enjoy their retirement years in Texas. Scott’s memories of his time in the missile silos were sharp, despite the passage of more than 55 years. Photo courtesy Jim Scott.

On February 12, 1964, the Air Force gave notice of their intent to decommission the Atlas-E missiles deployed across the country. The reasons given for the decision were both economic and pragmatic. Each Atlas missile in the Air Force’s arsenal cost a million dollars a year to maintain and operate. Each deployed Atlas missile required 80 men in support. Pragmatically, after the creation of the Atlas missile, the development of solid rocket fueled engines led to missiles which could be stored fully fueled and ready to fly, decreasing the time between the receipt of orders to launch and the rocket taking flight. Like the name implied, the Minuteman missile could be launched in less than 60-seconds from the receipt of an order. Annual cost of maintenance of a Minuteman missile was 1/10th of that of an Atlas rocket.

Despite the notice of the impending closing of the Atlas missile sites, it was not a decision that could be implemented overnight. Initially, the Air Force ordered the production of any new Atlas missiles halted, and a freeze on new members of the Atlas-E, Atlas-F, and Titan-1 (also decommissioned) missile squadrons was initiated. The Air Force then launched an intensive study on the decommissioning of the scores of surplus missile silos around the country.

On November 19, 1964, Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara announced the phase-out of all of the Atlas-E, Atlas-F and Titan-1 missiles in the American nuclear arsenal. While the Atlas-E missiles, the oldest of the three to be decommissioned, were only 38-months old, McNamara asserted that the “weapon systems were no longer supportable—either from requirements, cost, or manpower utilization standpoints.” The Air Force report continues, “The relatively vulnerable, slow-reacting Atlas and Titan I missiles had served their purpose in providing an initial ICBM deterrent and were now to be phased out. Less vulnerable, more easily maintained Minuteman missiles were in inventory in quantity at the end of July 1964, with a prospect of considerably more by the end of FY 1965. The large payload Titan II’s, although relatively few in number, would further swell the total of operational ICBS’s by 1 July 1965.” The report adds, “the cost of maintenance was about $1 million per year for each Atlas and Titan-1, compared with $100,000 per year for a Minuteman.”

The Air Force began planning for the impending decommissioning of the Atlas and Titan rockets. The phase-out was significant: it included 99 Atlas sites, 18 Titan-1 complexes (3 each), 153 launchers, and 221 missiles, including operational units, spares, and rockets in storage, testing, and at the Convair factory.

Initially, all of the spare, unused missiles were recalled for storage at Norton AFB in California. Those spares were transported by Air Force C-133 aircraft in short order. However, on December 24, 1964, all C-133 transport aircraft were grounded. As the Air Force could not predict when they would be permitted to fly, a decision was made to transport the remaining 149 Atlas and Titan missiles to Norton AFB by ground. The transport convoys could only travel during daylight hours, and the entire process of going to a missile site, loading the missile and transporting it to Norton and returning to its home base took 21 days.

One by one, the nine missiles were removed from the Forbes launchers and shipped to Norton AFB. The first Forbes missile went off alert on January 4, 1965, and the last missile in the arsenal went off alert on January 28, 1965. On February 8, 1965, the last missile shipped from Forbes to Norton. The 548th Strategic Missile Squadron stood down on March 25, 1965.

By April 29, 1965, less than four months after orders to transport the missiles were given, all 149 missiles had been moved by surface a total of 218,700 miles to Norton AFB with no accidents.

An Atlas-E missile is seen here being transported across the Kansas prairie. Just in front of the rear wheels is the Tillerman’s cabin where an airman rode who was responsible for turning the rear wheels of the long trailer.

The Air Force had spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the creation of the Atlas missile program and the deployment of its missiles in buried launchers hidden in rural areas across the country. To make matters worse, the missiles had only been in use for less than three years when the decision to decommission the Atlas was made. Extensive studies were initiated to determine if the military or any other government body might have any use for any of the closed missile sites. Several proposals were considered, such as an ammunition storage facility or in the case of the Atlas-F sites, the Air Force investigated the possibility of storing as many as a dozen Minuteman rockets in a single Atlas-F silo. In every case, it was determined that the site was unsuitable for its proposed use, or it was far more expensive to adapt the abandoned missile sites to a new purpose than new construction would be.

In the end, the study determined that there was little in the Atlas sites that was of any value to the Air Force, apart from some radio and electronic equipment, and the most important salvaged item, the two huge generators that provided power to the sites. On January 15, 1965, the Air Force announced that the 100 kilowatt-hour generators present at all of the missile sites would be salvaged by the Air Force to be used in different assignments. At the Atlas-E sites, the generators had been installed through an 8×16-foot access hole in the roof of the generator room. After installation, the hole was covered with an 18-inch thick concrete cap which was then covered with three-feet of soil. Removal was made through the same access hole, once the cap was removed. Cranes then lifted the somewhat disassembled generators through the access hole. An Air Force report dated June of 1966 reveals that 197 generators were removed from Atlas-E, Atlas-F, and Titan I silos, and 97 of those generators were serviced and then shipped to Department of Defense installations in Southeast Asia. The remaining 100 generators were placed in Department of Defense storage facilities.

This 100-kilowatt generator was one of 197 units that were removed from Atlas and Titan missile launchers in 1965. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

With the generators removed from the missile bases, there was little of value left for the Air Force, and the sites were turned over to the General Services Administration for disposal of surplus property. A notable exception was made with four of the Forbes missile launcher sites. Four of the sites were given to educational institutions, and thus excluded initially from the surplus property offered for sale. Site #2 at Worden was given to the Federal Aviation Administration for operations and records storage. Site #6 at Keene, Kansas was given to Unified School District 330 for a school site. Site #7 at Wamego was given to Kansas State College School of Engineering for a research lab. Site #9 at Holton was given to Unified School District 335 for a school facility site. The remaining sites were offered for sale to the public to the highest bidder.

The July 23, 1965 edition of The Hays Daily News reported on the opening of the bids for the Atlas bases at Schilling AFB, Altus AFB, and Forbes AFB. Concerning the Topeka bases they wrote, “Six bidders made 11 offers for nine sites at Forbes Air Force Base near Topeka, Kan. Irma and Max Wender, Detroit, Michigan were high with bids of $5,111 each for sites 1,2,3,5,6,7, and 9. They plan to use the silos on metal work manufacturing. Leon Stone, Tampa, Fla., bid $2,500 for site 1; Robert L. Grant, Merriam, Kan., bid $3,003 for site 2; Wayne P. Smith, Emporia, Kan., $4,500 for site 5; Mr. and Mrs. Jesse Johnson of Bushong, Kan., $500, also for site 5; and Holwick, Inc., Topeka, Kan., $3,750 for site 9. No bids were received for sites 4 and 8.”

The Air Force rejected the bids for the four sites that were given to educational institutions and the FAA, and sold the remaining five sites. With the exception of Site #7 at Wamego, all of the remaining sites became salvage operations which resulted in the removal of most of the salable metal.

Of the four sites which were given to educational institutions, only one, Site #9 at Holton was actually used for that intended purpose. USD 335 constructed Jackson Heights High School on the site of the former Atlas-E missile silo. The remaining three sites were ultimately transferred to private individuals. Site #6 has been a private residence for thirty years.

Jackson Heights High School, seen here, is located at the former Atlas-E launcher Site #9 at Holton, Kansas. Photo courtesy Association of Air Force Missileers.

All of the missile bases with the exception of the Wamego installation were prone to flooding from groundwater. Since none of the sites except Wamego had electrical power independent of the generators which were removed, all of the sites flooded a short time after decommissioning.

Categories: Biographies, Blog, Uncategorized, war stories

My father was a carpenter at the Keene missile site. He worked 7 days a week on 12 hour shifts for much of the time. During some portion of the construction, the workers were allowed to bring their families to the site for a tour. Dad brought my mother and children. I must have been about 11. I recall walking down the long tube that connected the living quarters with the control room and the missile launch area. Later, when USD 330 took ownership of the Keene site, a group of students in Terry Fanning’s Eskridge H.S. Vocational Agriculture classes made visits to salvage metal for some of our shop projects. I was among those students. On one trip, we walked into the control room and saw how the two missileers had separate controls/panels. Each panel having a key slot, that was explained to us students, as needed for simultaneous use to launch a nuclear missile. This was to prevent a launch by just one man.

LikeLike

I was a missile crewman assigned to the 548th SMS for nearly 3 years before they closed down the Atlas E missile program. This article was very accurate and brought back many memories. I actually re-visited our old missile site 9, in Holton, KS the farthest site north of Forbes. It was in the mid or late 60’s and it had been converted to a school for the local community. Nice ending really.

Some differences in my experiences was that there were not always security police resent on the site, but probably most of the time. We (enlisted) crew members did the top-side security checks and took along a walkie-talkie and an M-1 carbine. During the winter storms, it was not fun excursion, but necessary. We had great relations with the local community there and were welcomed in their stores and shops whenever we had the time to stop and pick up some snacks or sweets on our way to the underground ‘office’. They knew we were there and were thankful. Many of the names in the article I do remember, and the incident on site 4 with the security policeman’s death. Thanks for the article, brought back some good memories of a fine bunch or men and women and the reality of the cold war we were going through. I was fortunate to have been able to contribute my part during those times.

LikeLike