-by Greg Hoots-

John Bowers was born in 1865 in Minnesota, the son of a farmer. In about 1879 John left Minnesota to move to Topeka, Kansas where he took residence with his brother, Thomas, the owner of a brick manufacturing business. After ten years in Topeka, John Bowers departed on a two-year world tour, spending most of his time in Africa. Upon his return to the United States, Bowers learned the trade of photographer, and in 1896, he returned to South Africa where he opened a photography studio in Pretoria.

Bowers, then 31-years-old, married a 20-year-old British woman, Ellen Rose Bygott, whom he had met. A year later, their first child, a daughter was born. Barely a year had passed before the Boer War erupted in 1899, and as fighting was fierce in Pretoria, John Bowers and his family fled South Africa, traveling first to England before sailing to New York City in December of 1903.

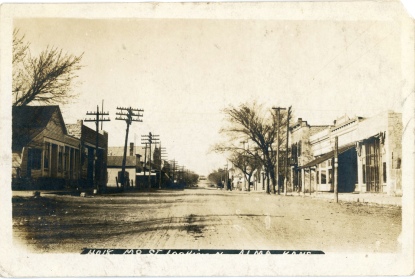

This 1907 real photo postcard by John Bowers looks south from the 200 block of Main Street of Maple Hill, Kansas.

The young family returned to St. Paul, Minnesota where John Bowers resumed his trade as a photographer, opening a studio in Minnesota and a second studio in Topeka in his brother’s building located at 409 S. Kansas Avenue. In 1906, John and his wife, Ellen, had their second child, a son, Walter. Later that same year, Bowers closed his St. Paul studio and moved to Spokane, Washington, where the family resided for just a short time before moving south to Long Beach, California, where he opened a new photography studio. John Bowers continued to travel to Topeka by train where he engaged in photographic excursions, taking views for real photo postcards, while selling the postcards to local merchants. Between 1907 and 1910, Bowers produced a large volume of postcard photographic views from Kansas, Missouri, Iowa, and Nebraska, as well his work in his Long Beach studio. Many of his California postcards were long panoramas which required extra postage because of their size. It is said that Bowers’ work in California included views from 22 counties.

John Bowers created a large portfolio of Topeka flood photographs during the famed 1908 flood. Most of Bowers’ views, such as this one taken on Norris Street, were taken in the badly flooded North Topeka.

Most of Bowers’ real photo postcards of Kansas were taken between 1907 and 1910, and they were numerous and noteworthy. The quality of his photographic work was a result of his utilization of good cameras coupled with his expertise in the darkroom. In Wabaunsee County, it appears that Bowers or one of his associates took numerous photographs of two of towns, Maple Hill and Alma, both located on the Rock Island route from Topeka. As Bowers’ views were numbered, it might be assumed that there were other Bowers real photo postcards taken of Maple Hill and Alma besides the ones currently inventoried.

This 1907 view of Missouri Street looks north from the 200 block. Notice that the new Meyer building (where the Wabaunsee County Historical Society Museum is located today) had been constructed when this view was taken, but the old Meyer building, next door to the south, was still in use.

The explosion of interest in collecting real photo postcards, beginning in 1908, fueled Bowers’ business beyond his dreams. While his Midwest real photo postcard business was booming, his Long Beach studio was even more successful. Bowers took a partner, photographer, Irchiro Asai, to assist him in the business, and in December of 1910, Bowers hired a third man, George Richard “Dick” Ward, a longtime friend of his wife from England, to assist him in his work. Ward moved into residence quarters located in Bowers’ Long Beach studio where Asai also resided. Bowers’ brother, Thomas from Topeka, was spending the winter at his brother’s home, living in a back bedroom in the house. The Bowers’ daughter was in boarding school, while five-year-old Walter’s bedroom was in the front of the house.

John Bowers’ specialty as a photographer was the creation of real photo postcards. While he produced scores of long panoramic postcards of California views, there are no known examples of panoramas in Bowers’ Kansas real photo postcards. Most of Bowers’ Kansas postcards bore the imprint on the reverse, “J. Bowers Photographic, London”, although there is no evidence that John Bowers ever operated a studio in London. It has been speculated by postcard collectors that listing his headquarters as being in London gave his business an air of sophistication. Bowers’ California postcards all bear the imprint, “J. Bowers Photo Co., Long Beach, Cal.”

This panoramic postcard, titled Santa Barbara From the Hills, bears the imprint, J. Bowers Photo Co., Long Beach, Cal. and dates from about 1910.

Bowers took pride in his darkroom work, evidenced by the quality of his postcard views. He designed and developed a machine which would print multiple images of a single postcard negative onto a long strip of photographic paper from a roll, which were then cut into individual postcards. On January 9, 1911, John Bowers submitted a United States patent application for the machine which he invented. Bowers installed the prototype of the machine in his Long Beach studio darkroom, and he claimed it to be a labor-saving device.

Seven days later after submitting his patent application, on the morning of January 16, 1911, John Bowers announced to his wife that he and Mr. Asai would be departing that day on a three-day business trip. Later, Ellen Bowers claimed that her husband had planned on traveling first to Oceanside and then to Escondido on a trip to collect past-due accounts, which would keep him away from home for three days. Such a trip was not unusual for Bowers, as he traveled when taking photos for postcards, and he still maintained a studio in Topeka. John Bowers, however, had other plans which he shared with no one.

This 1908 view of Mill Creek at the Maple Hill “Romick” crossing was taken by John Bowers.

Later in the morning, Bowers and Asai departed separately, the purported plan called for the two men to meet at Oceanside to do some photographic work, and then Bowers would continue alone to collect his accounts. In reality, after concluding the work in Oceanside, Bowers proceeded to a gun store when he purchased a 32-caliber pistol and a box of ammunition. He then returned to his home where he took a position in hiding outside where he could observe the comings and goings at his home. It wasn’t long before his wife departed alone, walking to her Eastern Star Lodge hall. Ellen Bowers was a trained musician, and she was the piano player for the lodge’s dances, one of which was being held that night.

Hidden in the bushes, Bowers loaded his new pistol with bullets and prepared to don his disguise which he would need later in the night. He slipped his gun in his overcoat pocket, and he removed his fedora, hiding it under a shrub, before placing a soft, green, short-billed hat which belonged to Mr. Asai on his head. The hat was too small for Bowers, but he pulled it onto his head, and he took a folded photographer’s cloak which he had carefully concealed inside his overcoat and placed it over his head, pulling the cloak around his shoulders, concealing his face below his eyes.

As darkness fully enveloped the night, John Bowers crept through the yard, hiding behind bushes and trees until he could peer into the windows of his house, seeing who was home. He was able to discern and identify his brother Thomas Bowers, his son, Walter, and Dick Ward. Then, the waiting game began.

The Eastern Star dance ran late, and it was almost midnight when the event ended and Ellen Bowers prepared to leave the lodge building. Another lodge member warned Mrs. Bowers about walking home alone, as the pianist was wearing expensive jewelry. Ellen Bowers then called to her home, asking young Dick Ward to come to the lodge and escort her home. Ward dressed and exited the Bowers’ home, walking quickly down the street, as John Bowers watched from behind the bushes next to his home.

John Bowers took many photos of businesses in Lawrence while operating his business in Topeka. This view of the Baptist Church dates from about 1908.

Ellen Bowers was waiting when Dick Ward arrived, and as a bright, full moon glowed in the California sky, she suggested to her companion that they walk home by way of the beach rather than Oceanside Drive. The couple strolled down the sandy beach in the moonlight, arriving at their beachfront home at about 1:00 am. As the couple approached the Bowers’ home, a dark figure of a man emerged from the shrubs near the house and ran across the yard and down Oceanside Drive. Mrs. Bowers urged Dick Ward to give chase to the intruder, and the young Englishman began following the stranger’s path down the beach road. John Bowers had too much of a lead, and soon, Ward lost sight of the late-night trespasser before returning to the Bowers’ home at about 1:30 am. Dick Ward normally slept in quarters located in the studio, a small building attached to the Bowers’ house; however, on this night Mrs. Bowers invited the English guest to sleep in the house with her, Walter, and Thomas Bowers, and Ward agreed. Five-year-old Walter Bowers normally slept on a couch in a small room adjoining the Bowers’ bedroom, separated by only a curtain. Ellen Bowers aroused her son, moving him to her room, allowing Dick Ward to sleep on the couch. Thomas Bowers occupied a small sleeping room at the back of the house. The Bowers’ fifteen-year-old daughter, Queenie, was not at home, as she lived at a boarding school operated by a convent in Pomona, California.

At approximately 2:30 am, Ward claimed that he was awakened by what he described as “a noise on the porch as though some person was fumbling with the lock on the front door.” The first thing that Dick Ward had done upon his arrival at New York from England was to go to a gunsmith and purchase a revolver. Concerning Mr. Ward’s possession of a gun, Mrs. Bowers later testified in court, “he always carries one…he got into the habit of it while living in Africa.”

This March 6, 1911 edition of the Los Angeles Times shows a photo of accused murderer, Richard “Dick” Ward.

Ward opened the front door, and stepped onto the porch, seeing the cloaked figure of a tall man standing in the moonlight. Ward later testified that he demanded that the man identify himself and his business at the residence, and the intruder did not reply. Ward’s story was unclear from this point. Initially, he said that the unidentified man raised a hand as if to strike him, and Ward raised his pistol and pulled the trigger, shooting the intruder in the forehead with the end of the barrel of the gun just inches from the victim’s head. In a later version of the story which Ward presented at trial, he claimed that instead of raising his hand as if to strike, the intruder dropped his hand as if to get a weapon from his pocket, which prompted Ward to shoot. Ward began telling this story after he learned that a gun had been discovered in the pocket of the dead man’s coat.

The Topeka State Journal ran this article titled, “His Fatal Error” in the January 18, 1911 edition of the paper.

The force of the gunshot knocked the intruder half-off the front porch, and the small green hat which the prowler wore was thrown some twenty feet into the front yard from the bullet’s impact. After killing the man, Ward immediately examined the body to find that it was, indeed, John Bowers that he had killed. Thomas Bowers testified that he was asleep in the back of the house when Ward and Mrs. Bowers entered his room, “saying that Dick had shot Jack.” Thomas Bowers hurriedly dressed and went to the front porch where his brother was sprawled across the steps. The elder Bowers, Dick Ward, and Mrs. Bowers lifted John Bowers’ body and carried it into the house, laying it on the floor in the room where Ward had been sleeping. Thomas Bowers took a pillow from the couch where Ward had slept and placed it under his brother’s lifeless head.

Mrs. Bowers attempted to call a doctor, but allegedly, she was unable to make a connection with the operator. Ward then departed the scene, returning with a physician, Dr. Buell. The doctor examined John Bowers and declared that the man was dead, saying there was nothing that he could do for the man, so he returned to his home, but not before he called the police, notifying them of the killing.

When the police arrived, they discovered Ward asleep in a window seat, covered with a blanket. Mrs. Bowers had returned to her bed and was asleep, as well. Officers at the scene later indicated that they thought it quite unusual and somewhat incriminating that the victim’s wife and the alleged killer had both taken a nap after the shooting.

Upon questioning by police, Ward insisted that he had not recognized the prowler and feared for his life and the lives of the others in the house from the menacing posture of the intruder. Ward was jailed awaiting trial, held in lieu of a $25,000 bond. Ward indicated that he had given the victim, John Bowers, all of his considerable savings to keep in the bank for the Englishman, as he had no bank account of his own in America. Thus, the accused contended, he was unable to post such a high bail. Mrs. Bowers’ brother, Walter Bygott of Redlands, California, hired attorney Will H. Anderson to defend Dick Ward against the charge of murder of Bygott’s brother-in-law, John Bowers.

Notice that the “new” Alma High School was still under construction when this 1907 Bowers’ photo was taken. The steps and sidewalks had yet to be constructed.

On April 12, 1911, Ward’s trial began in Judge Willis’ courtroom with Deputy District Attorneys Veitch and Horton representing the State of California and Will Anderson for the defense. The prosecution produced a wide array of witnesses including Thomas Bowers, Ellen Bowers, Irchiro Asai, Dr. Buell, three police officers who answered the call, an astronomer who testified as to the brightness and clarity of the moon on the night of the crime, and Bowers’ next-door neighbors.

The case of the prosecution was clear. They claimed that Mrs. Bowers and Mr. Ward had been having inappropriate relations, and further, that the infidelity was discovered by John Bowers who attempted to catch his wife and Ward in a compromising position. Ward, the prosecution contended, knew exactly who the “intruder” was, none other than his good friend and his lover’s husband, John Bowers. The autopsy had determined that the shot which killed Bowers was fired just inches from the victim’s face, and that in the bright moonlight, his identity would be easily discerned at that short distance. Prosecutors challenged the claim that the Asai’s green hat brim hid Bowers’ identity from Ward, as a prosecution witness noted that there were no powder burns on the hat, and when considering the location of the entry wound, it was obvious that the hat could not have been pulled down over Bower’s eyes as Ward claimed.

The state presented two witnesses in an attempt to prove that Ward and Ellen Bowers were romantically involved. Thomas Bowers testified that on one occasion he had observed Dick Ward leaving Mrs. Bowers bedroom in the middle of the night when John Bowers was out of town. John Bowers’ partner in the photo business, Irchiro Asai, testified that it was no secret that Bowers was extremely jealous and mistrusting of his wife, Ellen. More than one newspaper account describes Ellen Bowers as “a very attractive lady.”

This Bowers view of Kansas Avenue, looking north from the 300 block, was taken in about 1908. It’s obvious why this street is commonly called “the wide street” by locals.

For the defense, Will Anderson called the defendant, Dick Ward, to the stand to give his side of the story. Ward contended that he and John Bowers were good friends, and that it was John Bowers who had written him and asked him to come to America and join in his business. Ward was unshakable on cross-examination. As to the charge of excessive force, Ward explained that firing a gun at an intruder was a normal and accepted practice in South Africa, and that he did not think twice in his decision to shoot an intruder in his protection of Mrs. Bowers and the other occupants of the house. Ward’s position could not be shaken by the prosecutor, despite intensive questioning by Veitch.

At 4:30 pm, the case was given to the jury, and the panel deliberated throughout the night and well into the next day. In the middle of the afternoon on April 13, the jury reported to the judge that they were hopelessly deadlocked with an 8 to 4 split, without any possibility of any juror changing their vote. Judge Willis dismissed the jury and remanded Ward to the custody of Sheriff Hammel, pending a decision by the prosecutor to retry the case. Although it was not announced in court, as soon as the jury was released it became common knowledge that eight jurors voted to acquit Ward while four men had voted to convict.

The prosecutors were adamant in their decision to retry Ward, but this time the charge was manslaughter. Ward’s bail was reduced with the new charge to only $5,000, but no one would post the money for the British citizen.

The old Alma high school was abandoned when this Bowers photo was taken in 1907.

On May 8, 1911, Ward’s second trial convened before Judge Willis with the same prosecutors presenting their case. After the trial convened and the prosecution presented its opening statement, Judge Willis addressed the prosecuting attorney’s team, asking them if they had found any additional material evidence beyond that which was presented in the first trial. Deputy District Attorney Veitch replied that they had not, but that they believed that the evidence which was presented and which was still available was sufficient to convict Ward. Judge Willis expressed his disagreement, saying “that another trial on the same evidence would be ineffectual,” and he summarily dismissed all charges against Dick Ward and released the accused man.

After the end of the trial, Irchiro Asai claimed ownership of all of the photographic equipment from Bowers’ Long Beach studio, and he removed it and himself to Denver, Colorado where he established a business of his own. Virtually all of the money in John Bowers’ bank account was claimed by his acquitted killer, Dick Ward, who was successful in proving that nearly all of the money in the account was Ward’s, and that Bowers had only deposited it for safe-keeping. Ellen Bowers took a job as a nurse which she maintained for more than twenty years until her death.

Finally, there are some J. Bowers postcards which bear dates after his death in 1911. Those were not new merchandise produced after his demise, but were, instead, postcards which retailers continued to sell from their stock after the creator’s death in January of 1911.

Click on any image below to view in a gallery format or as a full-screen image:

Categories: Biographies, Blog, Photo Friday, Photographs

wow – amazed at the pics!! Thanks for sharing.

LikeLike

Thanks, Greg, for a great story. Your research is always impressive. Not related to my Bowers family, as we are descended from Robert Bowers through my immigrant Great Grandfather, Josiah Bowers of Hunden, Suffolk, England. Josiah came to the US in the early 1880’s to seek fortune first in Colorado, then settled in Osage County, KS near Barclay. He was a farmer there and near Admire before moving to Topeka, KS where he died at the home of his youngest daughter in 1947.

LikeLike